I’ve been thinking a lot about leadership transitions lately. With a new mayor, four new school board members, and new-ish superintendent, it would be hard not to.

Our natural tendency is look for immediate change, expecting campaign promises to be fulfilled overnight. Right now, we’re waiting for potholes to be filled, wondering if the changes to the NCNAA programs will be reconsidered, and generally wishing that tomorrow will be just a little bit easier to raise our kids in this City. We hold out hope for instantaneous change even though we know deep down it doesn’t work that way. We know change happens slowly, especially in massive bureaucracies like City government and the school district, but we can’t resist searching for clues or feeling angry when we can’t find them.

Maybe I’m too generous, but I think, in most cases anyway, that our leaders actually intend to follow through on their promises. They believe they have the answers until they get the job and realize there are a million reasons why things are the way they are and it wasn’t just that their predecessor was lazy. Or, maybe, something unexpected happens that must be addressed first. A pandemic. A sinkhole. A court case. A budget shortfall. A controversy.

I’ve been in and around politics long enough now to know that it’s not really fair to judge leaders on how strictly they uphold their promises. Instead, I assess them on how they respond when things go wrong, who or what they choose to blame (or if they play the blame game at all), and how well they communicate with the public about their policies, plans, and timelines.

At last Tuesday’s school board work session, Superintendent Borishade opened the meeting with a lengthy statement about the challenges facing the district and the importance of strong leadership in addressing them.

“As we move forward it is essential to acknowledge the challenges and opportunities that lie before us. For the past decade and a half our district has faced several issues that have impacted our stability and from there these challenges proceeded my tenure as superintendent which began on February 18, 2025. However, I am confident that by working closely together we can continue to addresses these issues and restore the foundation upon which SLPS will thrive on.”

—Dr. Borishade, April 22, 2025, video, (emphasis mine)

Later that evening, she released a written statement to press and employees reiterating the same themes.

“As Superintendent since February 18, 2025, I have been surprised by the systemic issues that have plagued our district for years. These challenges, as highlighted in recent reporting, are not new, but their impact is deeply concerning.”

—Dr. Borishade, April 22, 2025, statement, (again, emphasis mine)

If we (the public, the “regular” people) have a tendency to expect change to happen immediately, then our leaders have a tendency to remind us that they’re new, how they inherited these problems from their predecessors. That’s true, of course, but the leaders of today become the predecessors of tomorrow. The choices they make now will become the excuse for someone else’s inaction in the future.

For at least 75 years, education policies have been reactionary and reactive rather than strategic and forward-looking.

And, for 75 years, City and education leaders have avoided working together in meaningful ways to design a public education system that treats schools for what they are: valuable city infrastructure.

There are a lot of images in this post and Substack is warning me that some email apps will truncate this email. To read the entire post and see all the images, please be sure to click on “view entire message” if prompted by your app.

2020-2021

You all know this part. Back in 2021, the SLPS school board closed schools even as several charter schools applied to open. I spent a lot of time pushing for a moratorium and a citywide plan, pitching them both as a way to bring leaders together from across the city and across sectors to implement policy solutions that would minimize the need to close schools in the future.

It's easy to rifle through the popular list of villains — Alvarez & Marsal, the SAB, Dr. Adams, Dr. Scarlett, absent city elected officials, punitive state legislators — and choose a few to blame or to think that if we’d only get rid of all the charter schools or magnet schools or gifted schools and redirect those resources back to our neighborhood schools then we’d rebuild the system to its original glory.

“There just isn’t a coherent, cohesive plan for what education in this city looks like. There’s so much money that’s pouring in to sustain this fragmentation — buildings and transportation, duplicative services, administrative salaries, marketing, and it’s coming at the expense of the kids. What we need to do is reinvest in the schools we have.”

—Dorothy Rohde-Collins, 2021

The reason I know it’s easy is because I fell into that trap too. I blamed charter schools and the mayor and the aldermen and anyone else I could think of for the district’s demise. I did what any good spokesperson would do and I loudly defended the organization I represented, demanded that everyone reconsider their opinions.

“With students, Black and white, continuing to leave the district, it is essential that city and district leaders work together to develop joint strategies for what the future of public education will look like in the city…”

— St. Louis Post-Dispatch Editorial Board

I don’t regret it, it got the idea of collaboration between city and education leaders back into the discourse after all, but I do wish I’d been more aware of our city’s history and just how long we’ve been caught in this cycle.

So, let’s go back in time together, peel back the layers and try to understand how we got here. I don’t pretend to have all the answers, or even any answer, but I do remain committed to trying to find them.

1980s

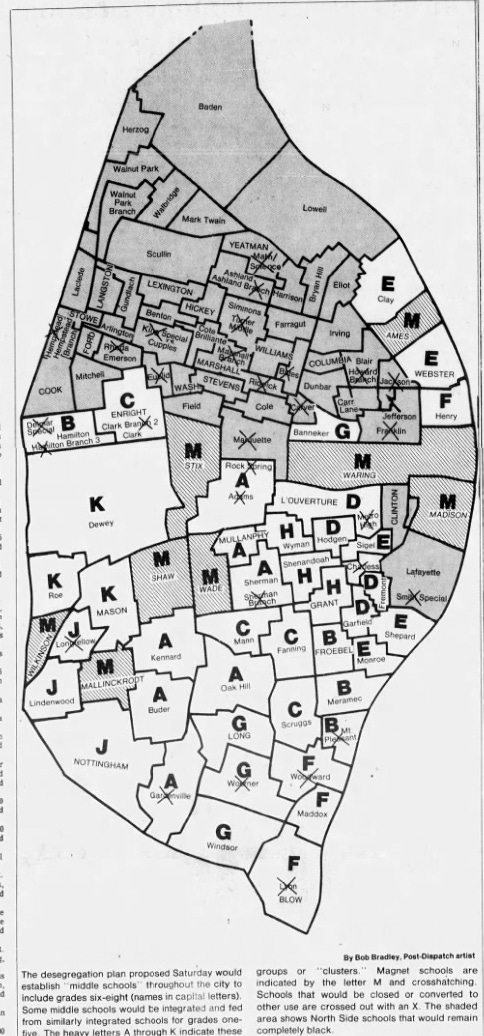

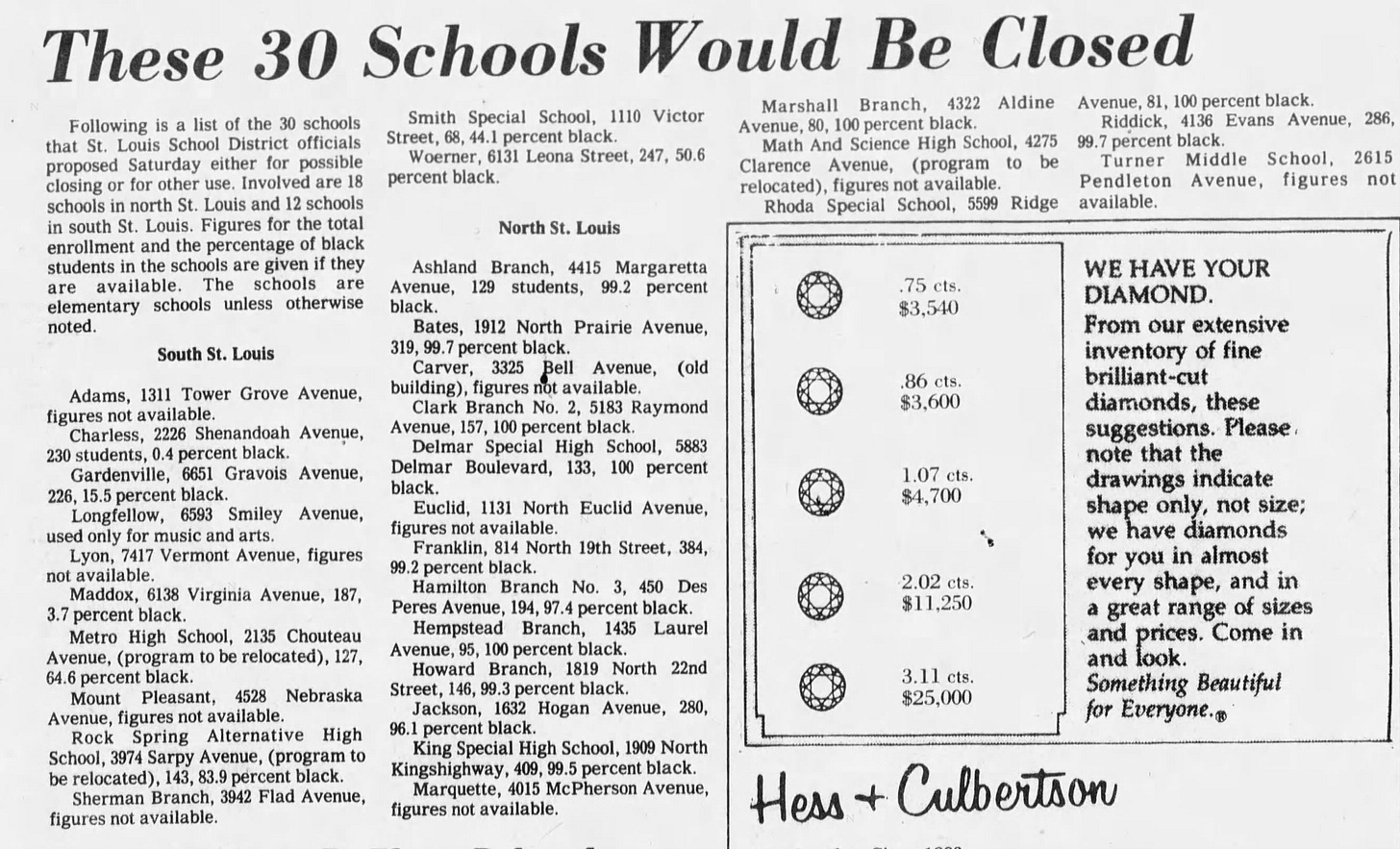

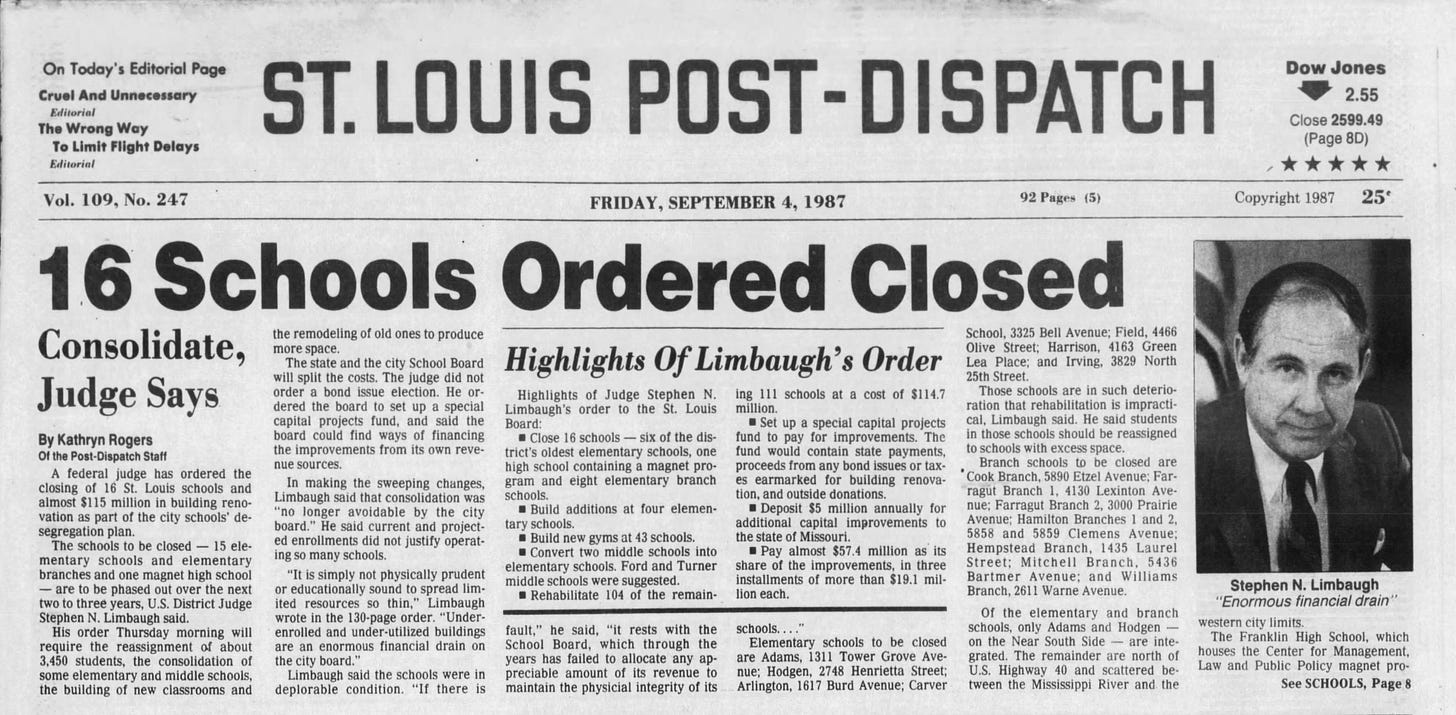

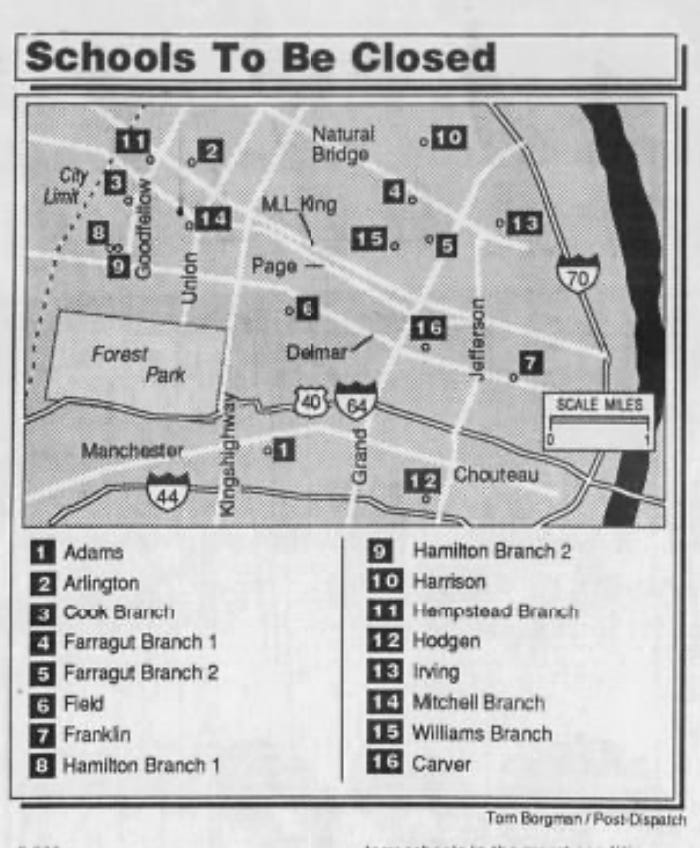

The 1980s were quite a time. The city’s population was plummeting. SLPS was still trying to figure out how to desegregate schools amid numerous court orders. And, despite launching a massive multi-year process to develop a strategic plan for the district to respond to shrinking population and a declining tax base, so SOOOO many schools closed. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions as to if any of these policy decisions left us better off.

“The relationship between the city and its schools is interdependent. The population of the schools reflects the population of the city. City resources are school resources. Growth of the city means growth of the schools. The schools should attract young families, prepare students for the job market, and enhance the image of city life. The relationship between city and schools is symbiotic: the growth of one is inextricably dependent on the health of the other. The findings of the CAC point to an urgent need for school leaders to join the Mayor of Saint Louis, the Board of Aldermen, the Governor and the State Legislature in bringing the paths of the city and its schools together in a direction of growth.”

— SLPS Community Advisory Committee, Long Range Plan Executive Summary, February 1985

1960s

But the challenges of the 1980s should not have come as a surprise to anyone. The population boom of the 1940s and 1950s led to a public school enrollment boom in the 1960s. Except there weren’t enough schools for all the students. Voters failed to pass bonds to build new schools and classrooms remained overcrowded. Newspaper coverage from the time indicates some gym classes were so crowded kids couldn’t fully extend their arms without hitting another student. Branch schools opened in old churches or other buildings available for lease and children were transported across the city to fill every available seat. And all of these policy decisions were made worse by the implicit and explicit racism of the time.

It’s been a long time since the public school system was “right sized” for St. Louis and the erosion of neighborhood schools began earlier than we might initially think.

“Three times St. Louisans have failed to return the necessary two-thirds majority to provide desperately needed funds for new schools and fire safety concerns. Thousands of children go to school in buildings hopelessly lacking in facilities for modern learning programs. Thousands board buses daily to attend schools as far as ten miles from their homes.”

—SLPS Board of Education in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1961

By 1967, things were so bad that SLPS published a report to describe the litany of problems facing the school district: a budget limited by local property tax revenues bound by decreasing assessments; skyrocketing enrollment; insufficient facilities; unsustainable student-teacher ratios; a state government unsympathetic to the plight of the district and city; a growing parochial school system; and an increasing number of students living in poverty.

“The St. Louis Public Schools have been in pain for ten years. The City is in pain, too, for the school system is a reliable barometer of the community which it serves. We are in good company. Every city school system, and, consequently, every big city in the United States hurts. In fact, most of them hurt worse than we do.” (p. 1)

“Obviously, if the city is to reinvigorate itself, or even survive, it must offer some inducement for the return of substantial numbers of those who have fled. All who have a stake in the prosperity and health of the city must realize how imperative it is to invest heavily in that which is the basic security for good family living a strong and vigorous public school system with an instructional program of such quality that it will inspire hope for the future of our children.” (p. 18-19)

“Yes, the St. Louis Public Schools have been wounded and are still suffering pain, and they can relapse slowly into mediocrity and desolation. The community will go as the schools go, for the schools are the barometer of the community.” (p. 21)

—SLPS, 1967

1950

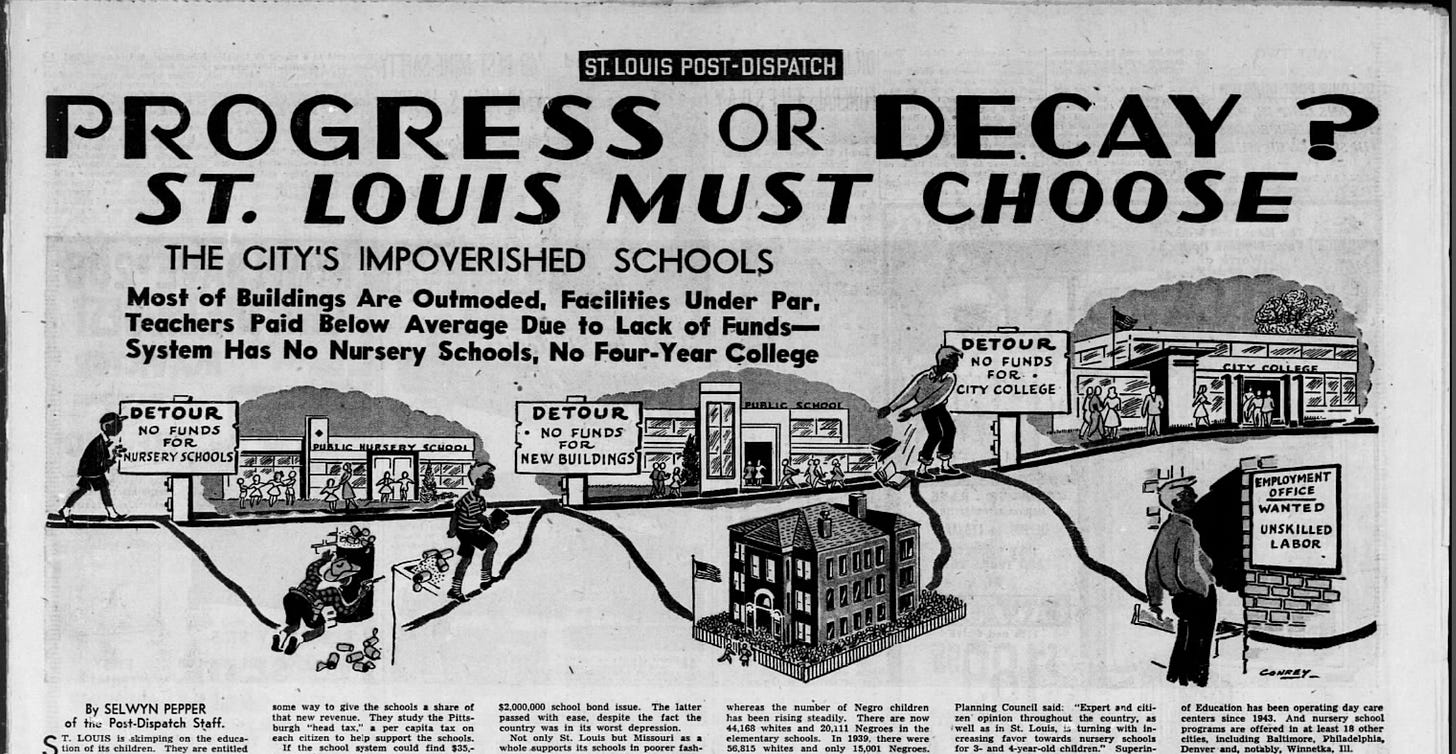

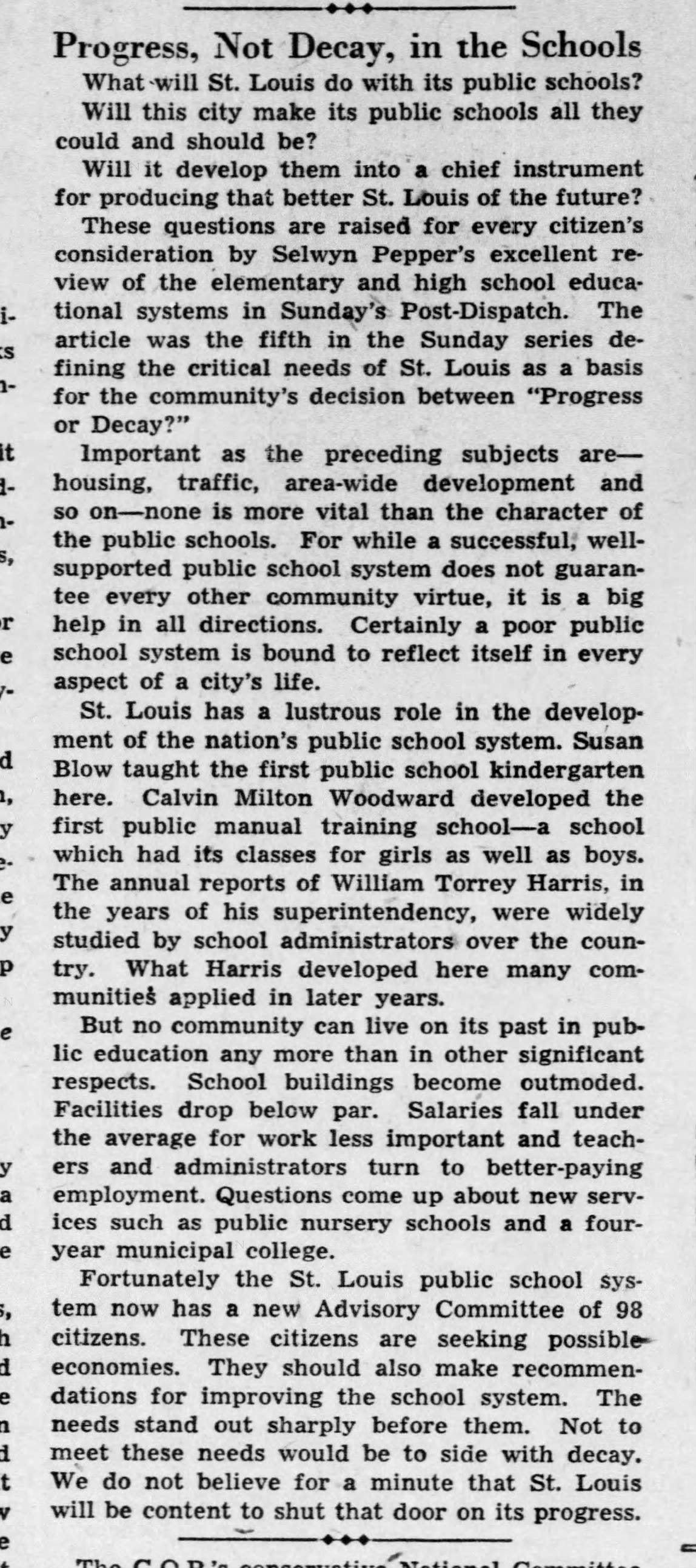

But the problems of the 1960s shouldn’t have been a surprise either. They were all identified the decade prior in a bold St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial series. Indeed, the writing’s been on the wall (or more accurately perhaps, in the pages of the daily newspaper) for 75 years.

“If St. Louis is to give its children better educations, if it is to prepare its citizens to meet the problems of today's complex society, St. Louis must give more financial support to the public schools. The city's most valuable resource is its children; their ability to contribute to the city's future will depend largely on the education St. Louis offers them.”

— Selwyn Pepper, 1950

“Not to meet these needs would be to side with decay. We do not believe for a minute that St. Louis will be content to shut that door on its progress.”

— St. Louis Post-Dispatch Editorial Board, 1950

Yet content we were and content we are. The door remains closed on progress. Seventy-five years later and it’s hard to tell what, if anything, has changed. There have been so many warnings about the interconnection between the city and its schools; population and enrollment; past and future. We ignore them every time.

It’s hard to say where all this started and it’s even harder to know where it all ends. Maybe we will be the generation that gets it right, interrupts the cycle, stops the madness. Or maybe, 25 years from now, we’ll be watching it play out again.

The archival work and analysis behind this post costs both time and money. If you are able, please subscribe to City Reform at a level that fits into your budget to help show support for the work. Paid subscriptions help me cover my costs. If subscriptions aren’t your thing, you can add a few bucks to my coffee fund. Thanks for reading!

As usual, this is a fantastic blog piece ,very informative! Thank you for your transparency and insightful writing.